Amy Poehler says one hard and fast hiring rule is key to her success as an actress, producer, and director: Don't hire or promote talented jerks.

Amy Poehler said at this year's Indeed Interactive conference in Austin, Texas, "The most talented people I've worked with are the easiest to work with. There's the occasional genius who can't figure out how to collaborate, but they're rare."

In other words, true "geniuses" in the workplace do exist. Still, they're few and far between – so the chances that every workplace bully is a "genius" are not likely (hence the consistent air quotes around the word "genius"). Even so, people don't need to be difficult as proof of talent. The trope of the "jerk genius" likely unconsciously leads us to underestimate the talents of people who may be introverted or respectful.

So why do we gravitate towards bully geniuses? After all, world-renowned entrepreneurs Steve Jobs, Jeff Bezos, and Elon Musk could all fall into that trope. And you could list at least one or two people at your organization who may be fantastic at pitching new ideas and pushing projects forward, but at the cost of degrading employee morale.

How we've conventionally hired and promoted talent favors the jerk genius. Here's why.

Why Difficult People Get Hired and Promoted

To understand why we keep putting jerk geniuses on a pedestal, we need to examine the hiring and promotion patterns we're so comfortable with.

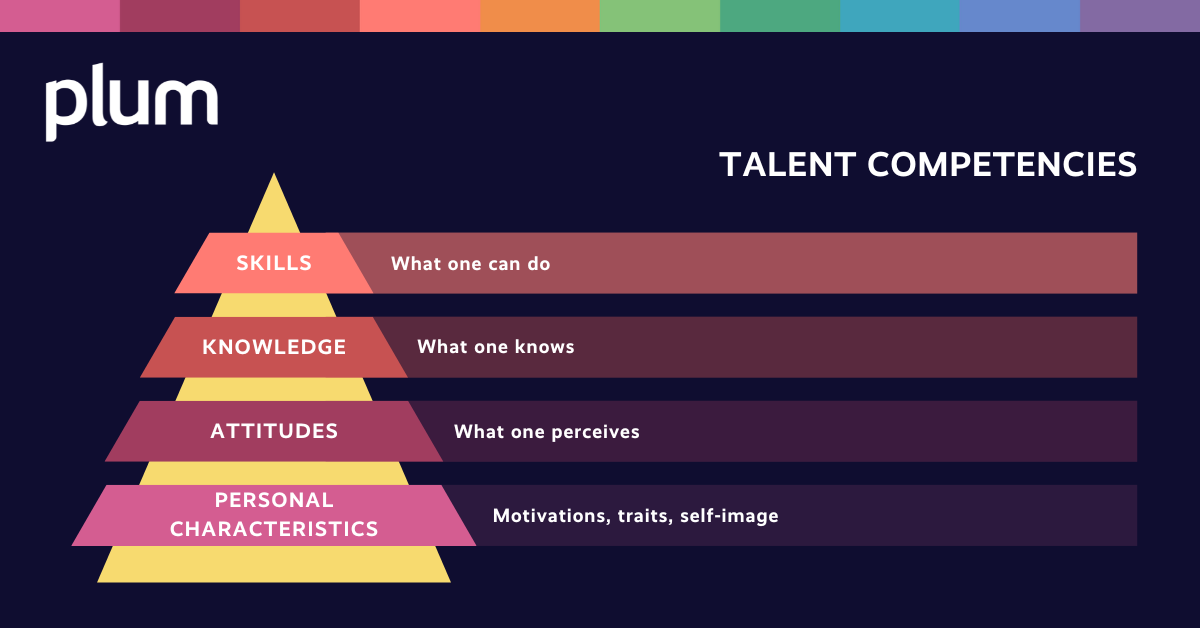

Whatever steps are involved in your hiring (resumes, phone screening, number of interviews, pre-employment assessments) or promotion (managerial nominations, performance reviews) processes, the criteria you're looking for in your selection decisions likely all boil down to the same concept—skills and knowledge.

According to Marcus Buckingham and Curt Coffman's model, skills refer to the how-tos of a role, whether you know how to weld, create spreadsheets in MS Excel, code in Javascript, and so on. Knowledge refers to literally knowing something, which can usually be quantified in a degree or designation, like a CPA, MBA, or PhD.

We may get a little starstruck by someone's credentials. In the past, hires and promotions were based on who had the most experience or the highest level of education (if the manager wasn't hiring from within their own network). But, as HR and people teams have become increasingly data-driven and employee-centric over the past decade or two, it came to light that the cause of most employee turnover – voluntary and involuntary – was not due to the employee's skills and knowledge but because of a previously unquantifiable "X factor" that had to do more with an individual's attitude and behaviors. Many organizations began to label this X factor "culture fit."

Could Hiring for Culture Fit Help Us Find Less Jerks?

Hiring for culture fit emerged as a revolutionary idea and was praised as a competitive advantage for many organizations. It felt like a step in the right direction – if the #1 cause of turnover in an organization was due to a person’s behavior or personality, couldn’t this problem be solved by asking questions like, “Will this individual integrate smoothly into this team/organization?” “Will the team dynamic be seamless or awkward?” “Will I like working with this person?”

These aren’t bad questions to ask in and of themselves, but there has always been one glaring problem—talent acquisition and talent management teams have not had the data to answer such questions. This means that hiring for culture fit has been based on decisions made with “gut feel,” which has resulted in biased and unpredictable talent acquisition practices.

Facebook, for instance, has prohibited interviewers from using the term “culture fit” as a blanket term when providing feedback about a candidate. Interviewers were using the term to select people whose personalities and backgrounds maintained the status quo—consciously or unconsciously. In other words, the term culture fit was being used to mean “just like us.”

How does the perpetuation of hiring for culture fit as selection criteria relate to terrible geniuses? Two ways: first, since there are already plenty of these genius stereotypes in managerial positions, a culture fit mindset will only result in difficult jerks hiring and promoting more difficult jerks. If a workplace culture is already toxic with bullies, hiring for culture fit will only compound the problem.

Second, without the data to back up our decision-making, anyone (office jerk or not) can make biased decisions based on preconceived notions that difficult people are high performers—when, in reality, they may just be insecure.

Hiring for Culture Fit the Right Way

So, the question still remains: how can you avoid hiring difficult people?

The key lies in sound, scientifically backed talent acquisition processes.

For decades, recruiting has relied on the aforementioned gut instinct, where recruiters decide who will best fit in with the company and role based on the 30–60-minute impression they get from an interview. Unsurprisingly, this doesn't provide accurate insight and can lead to a workplace culture where negativity is the norm.

The first step in remedying this is determining your workplace culture. Despite culture being one of an organization's most important characteristics, few companies have a complete and accurate view of what values their employees experience each day. If you don't know where your corporate culture is, it is impossible to take action to bring it to where it needs to be.

This creates issues in hiring for culture fit, as you may be bringing in people who fit a toxic culture that is not conducive to team success and productivity.

Layering in Talents for Culture Fit

However, cultural fit is only one side of the equation. At Indeed Interactive, Amy Poehler said, "When you're building a set, for example, you're all going to be in this situation together. I will absolutely choose someone that is collaborative, responsive, responsible, and highly recommended over someone that's a genius, every time."

Some people might call these traits (like collaboration and responsibility) "soft skills," but there's really nothing "soft" about them. Studies validated by Industrial/Organizational Psychologists have uncovered that these dimensions can predict someone's performance in a job far better than education and experience. That's why we at Plum call them talents. Talents are the third part of Buckingham and Coffman's model. Whereas skills and knowledge refer to a specific set of learned activities required for the job (e.g., typing, brain surgery), talents are recurring patterns of thought, feeling, and behavior.

Through psychometric data, talent acquisition and management teams can now access an objective, universal dataset that enables them to quantify someone's potential in a role. Hiring teams and managers no longer need to rely on unconscious biases to make great hiring and promotion decisions – which in turn gives less power to the difficult person who gets by with a "genius" façade, whether or not it's reflective of their inherent competencies.

So, all in all, we agree with Amy Poehler. People don't need to cause a lot of friction in your organization to prove their abilities – we have psychometric data for that. Measuring talents like communication, teamwork, and leadership takes power from the "geniuses" who are difficult for the sake of being difficult and puts it in the hands of actual top performers.

It is also critical to fully understand your organization's culture and how any new hires will contribute to the overall dynamic. We agree with Amy Poehler and believe this will result in a workplace shift from toxicity to an environment that fosters employee well-being, positively impacting employee morale and productivity.

Hiring for Culture Fit with PlumThrive

Although understanding your company’s culture and the talents of your employees is critical to success, we know that this is far easier said than done.

That’s why we launched the most comprehensive talent operations solution on the market. Plum provides deep insights into all aspects of your corporate culture, the talents of each employee, and more. This ensures you have the accurate data to hire people who fit your ideal corporate culture and have the skills they need to flourish in their roles.

Book a time with one of our experts to stop hiring terrible geniuses and start hiring people who will usher in a new era of productivity and success for your organization.